This is one of those “bird’s eye view” surveys. What I’d like to do is to give you an overview of a part - a rather large part - of the repertoire to put some well-known pieces of music into some sort of context. In this case it’s the operas of Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924).

There are arias from some of Puccini’s operas which are very well-known. I only need say the words “Nessun dorma” for you to realise what I mean, but English titles such as “Your tiny hand is frozen”, “One fine day” and “Oh my beloved father” also apply to arias from Puccini operas, and all these are much-loved and often-heard. But what about the other operas? While a handful of Puccini’s twelve operas are among the most regularly-performed today, there are others which are almost never heard. In this post I want to take you through the Puccini operas in chronological order and, I hope, give you an idea of where the really famous ones fit in, and what the little-known ones are.

All of Puccini’s operas can be heard - and usually viewed - nowadays on YouTube, a privilege I couldn’t have even dreamed of when I was a student. As I go through the operas here, I’ll share a link to a complete performance of each opera (usually a video of a staged performance), and also a link to an extract, if you’d prefer to have just a sample of each opera as you go.

Giacomo Puccini was a fifth generation composer. Based in the town of Lucca, not far from Pisa in north-western Italy, the Puccinis had a long and respected history as a dynasty of composers for the church and, later, the opera house. Giacomo Puccini Snr was born in 1712. His son Antonio was born in 1747. Antonio’s son Domenico was born in 1772, while Domenico’s son Michele was born in 1813. Michele’s son, the famous Giacomo Puccini, was born in 1858 and he wrote his first opera, Le villi, in 1883 as an entry in a competition. It didn’t win; it didn’t even rate an honourable mention. But a group of the 25-year old composer’s friends raised the money for the work to be performed in 1884 at the Teatro dal Verme in Milan.

Even though Le villi contains some attractive music, it gives little indication of the greatness to come, and it's hampered by a very poor libretto (libretto literally means "little book" and in opera it refers to the text which the composer sets to music). It has not held a permanent place in the repertory. While the initial performances were successful for the young Puccini, and even though it earned him some much-needed income, Le villi was soon forgotten.

His second opera - unlike Le villi - is a full-length work in three acts. Called Edgar (stress on the second syllable in Italian), the librettist was Ferdinando Fontana, who had also written the text for Le villi, but Puccini’s trust in yet another inept libretto was misplaced. It was to be the last time the composer set an opera text without question, and while Edgar gets closer to the mature Puccini, and again contains interesting moments, it is a pale reflection of the famous works to come.

Edgar was not greeted warmly on its premiere in Milan (at La Scala no less) in 1889. More importantly, though, Puccini learned a lot from his first two operas, and especially from his hitherto unquestioning acceptance of librettos. His next opera, Manon Lescaut, was written in the full knowledge of Massenet’s French opera on the same subject (called Manon) which had premiered in 1884. No less than six people - one of them Puccini - had a hand in the shaping of the libretto, to the extent that no-one is credited in the first edition of the score with writing the text. Puccini demanded rewrite after rewrite, but the results speak for themselves. Manon Lescaut was a stunning advance on Edgar, and its premiere at the Teatro Regio in Turin in 1893 was an enormous success. One critic wrote, “Between Edgar and this Manon Puccini has vaulted an abyss...Manon is the work of a genius.” Posterity has felt similarly, making Manon Lescaut the earliest of Puccini’s operas to hold a regular place in the repertoire.

The next three Puccini operas are among the most frequently-performed operas in the world. It’s amazing to think that once he had found his voice, Puccini then wrote three very different but powerfully successful works which have never been out of the repertoire in the century or so since they appeared. Interestingly, the same team of librettists - Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica - were responsible for the texts for all three.

While writing Manon Lescaut, Puccini wrote to his brother that his next opera would be about the Buddha (a subject also considered by Wagner, interestingly). As it turned out, Puccini’s next opera was inspired by a French novel by Henry Murger, about a group of down and out artists living "bohemian" life to the full in a Parisian garret. La bohème (The Bohemians) was first performed in Turin in 1896 and it’s a melodic, dramatic, powerful and moving work containing some of the greatest tunes in all opera. Rodolfo and Mimi’s arias in the first act are often heard separately, as is Musetta’s in the second. A stunning moment (linked in the extract below) which often gets overlooked, though, is the end of the third act, a quartet for the two pairs of lovers, one of which is arguing while the other is sadly agreeing to part...but just not yet.

Among those who admired La bohème was Debussy. He is supposed to have said to Manuel de Falla, “If one did not keep a grip on oneself one would be swept away by the sheer verve of the music. I know of no one who has described the Paris of that time as well as Puccini in La bohème.”

Puccini’s ideas for his operatic subjects came from many different sources. In Bohème it was a novel; for his next opera it was a play which was at the time very popular. Victorien Sardou’s play La Tosca was a vehicle for the famous Sarah Bernhardt, and she toured in the play all over Europe. Opinion is divided as to whether Puccini actually saw her in the play, but the powerful (and at times violent) drama of this woman destroyed by forces outside her control clearly gripped Puccini and produced an opera quite unlike La bohème. Gone is the sentimentality, the pathos and the desperate sadness. Instead we have a political thriller based on actual historical events with threats of rape, a torture scene, an execution and one of the most famous operatic suicides of all time. It contains the traditional soprano-tenor-baritone triangle, but unusually, all three are dead by the end of the piece. Joseph Kerman called Puccini’s Tosca a “shoddy little shocker”, while Benjamin Britten was “sickened by the cheapness and emptiness” of Puccini’s music. That may be so, but the torture scene (linked in the extract below) still gets me every time.

Tosca was first performed in Rome - the city in which the story of the opera takes place - in January 1900. The critics were shocked by it, and the torture scene was especially singled out for negative comment. Still, Tosca’s subsequent history has been far from shoddy; there can hardly be an opera company in the world today which doesn’t have it in their repertoire.

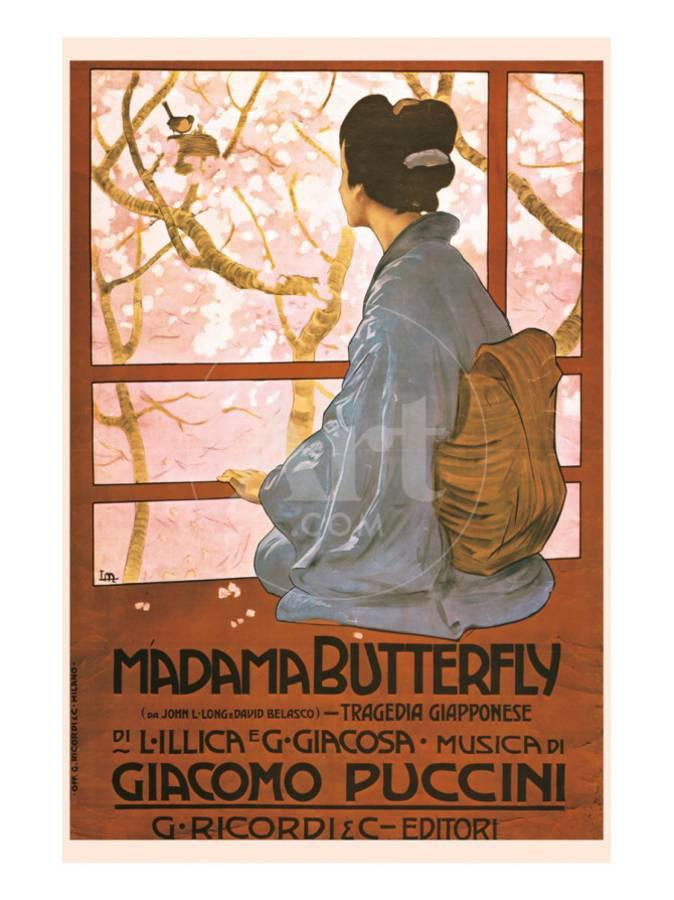

While he was in London to attend the English premiere of Tosca at Covent Garden (six months after the first performance in Rome), Puccini went to see a play. It was by the American playwright David Belasco, based on a story by John Luther Long. Even though the play was performed in English - a language Puccini didn’t speak - he was very moved by the plight of the abandoned Japanese girl who was the central character in Madame Butterfly.

In this way Puccini encountered the subject for his next opera. He had the play translated into Italian and again Giacosa and Illica set to work fashioning an operatic libretto for the composer as they had done for La bohème and Tosca. As usual, Puccini demanded fine tuning, major overhauls and rewrites, but eventually the new work, known in Italian as Madama Butterfly, was premiered at La Scala, Milan, in 1904. The original version was a failure at the premiere and Puccini made numerous rewrites over the next two years. There are in fact several discrete versions of he piece. Again Puccini surprised his audiences, with an exotic (that is, non-European) setting and subject, but the theme of a woman destroyed by circumstances outside her control - encountered in Manon Lescaut, La bohème and Tosca - continues.

Butterfly’s death scene (linked in the extract below), where she bids farewell to her little son before blindfolding him and killing herself, remains to this day one of the most moving scenes in all opera.

Puccini was to return to an Asian setting later in his career, but for an Italian the setting of his next opera was no less exotic. He considered and rejected subjects as diverse as The Hunchback of Notre Dame, three one-act operas on Russian subjects as a vehicle for the famous bass Feodor Chaliapin, and Marie Antoinette. But it wasn’t until he was in New York (to supervise the American premiere of Butterfly) that he found the subject for his next opera. Again, it was a play in English, and again it was by David Belasco, called The Girl of the Golden West.

The play was developed into an opera libretto by Guelfo Civinini and Carlo Zangarini and it was decided that a literal translation of the English title into Italian was too long. The “golden” aspect was removed, leaving simply La fancuilla del west (The Girl of the West). The story is set in the American wild west, specifically in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California during the gold rush of 1849-1850. The premiere took place - appropriately - in America, at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in December 1910. It was in fact the first world premiere in the Met’s History.

Fanciulla is perhaps Puccini’s most “impressionistic” score; many saw the influence of Debussy. It’s very “though-composed”, with little in the way of stand alone arias or set pieces. What arias there are tend to be very short...

After a very successful premiere and subsequent performances in the United States, Covent Garden and eventually Italy, Fanciulla has not been as highly-regarded as other Puccini operas. It is without doubt a beautiful score (a performance I saw at the Met in New York in 2018 was an utter revelation), but the spectacle of people dressed in “western” gear singing in Italian has unfortunate resonances of the spaghetti western for many people. On a musical level, the very fluid nature of the piece, and the fact that arias from the work are not easy to extract and perform on their own, has probably meant that Fanciulla has had less of a chance to shine, which is a pity.

Puccini’s next opera is even less well known, and far more widely denigrated. Again, after Fanciulla, he considered an amazing range of subjects for his next opera. He looked at German writers like Hermann Sudermann and Gerhart Hauptmann; he considered Oscar Wilde’s Florentine Tragedy and Blackmoor’s Lorna Doon, and much else. The idea of composing three one act operas for performance in a single evening also resurfaced, although the Russian idea was abandoned. In any case, Puccini’s journey to Vienna for the Austrian premiere of Fanciulla was the catalyst for his next work.

He received a commission to compose a Viennese operetta (like Die Fledermaus by Johann Strauss II) and the fee offered was staggeringly high. Eventually, after a number of false starts, the so-called operetta came to be written although it’s not an operetta in the Viennese sense. Operetta has spoken dialogue between musical numbers. What Puccini eventually wrote was a light opera on a bitter-sweet theme, sung throughout (that is, there's no spoken dialogue), and designed to be performed in either German or Italian. Called La rondine (The Swallow), this opera lacks the gut-wrenching power of the better-known Puccini works, but neither is it a comedy in the sense of Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier either. It’s just very different and requires a different sort of approach from audiences. The best-known aria (“Chi il bel sogno di Doretta”, linked below) is often heard in concerts but in the opera it’s really a duet of sorts.

The premiere of La rondine, planned for Vienna, was interrupted by the first world war and eventually took place in Monte Carlo in 1917. By that time his next project was well and truly underway, and this was the fulfilment of the three one act operas idea which had been on his mind for years.

Called Il trittico (The Triptych), the "work" consists of three very different stand-alone operas, each lasting less than an hour. It's rare these days for the composer's idea of performing the three works on a single evening to be observed; taken together they make for a rather long night, especially for the orchestra. It's more common these days for just two to be performed.

Puccini drew on a play for the first, a dramatic story called Il tabarro (The Cloak). A totally original story formed the basis of the second, a sentimental tragedy set in a convent called Suor Angelica (Sister Angelica). The third - Gianni Schicchi - is an uproarious comedy based on a few lines from Dante’s Divine Comedy. The premiere took place at the Met again, in December 1918, after the hoped-for premiere in Rome had to be abandoned due to the first world war.

Puccini used three very different musical languages to set the three very different stories in Trittico. Tabarro is bleak, dark and guilt-ridden; it ends with a horrible confrontation between a jealous husband, his unfaithful wife and the body of her murdered lover. The earlier duet between the wife and her lover (linked in the extract below) is one of Puccini's finest.

Suor Angelica deals with death but in a very different way. Sister Angelica’s guilt over the shame she has brought on her family, and her discovery that her son is dead, results in a suicide accompanied by a heavenly vision of redemption and forgiveness. Angelica’s tragic aria (linked below) about her little son, dying without his mother, is the centrepiece of the opera.

Gianni Schicchi ends the night with a silly romp, Puccini’s mini-Falstaff in a way, but one which shows the composer’s hidden gifts as a composer of comedy. The story, of a clever rogue deceiving others in order to make it possible for his daughter to marry for love, is brilliant. The daughter, Lauretta, has already blackmailed him emotionally with the famous “O mio babbino caro” (O my beloved father, linked below), but the wise dad helps her get her man by outwitting a large group of people, who are pretty upset to say the least!

Around the time of the premiere of Il trittico, Puccini turned sixty. Again several subjects were considered for his next opera, including one based on a character from Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, but his choice eventually settled on another exotic - and Asian - scenario. The play on which it was based was by Carlo Gozzi and dated from the 1760s. It had also been set as an opera by others over the years, as well having incidental music written for the play by composers such as Weber. But there can be no doubt that Puccini’s treatment of the Chinese princess Turandot is the most famous musical incarnation of the story.

Turandot was destined to be Puccini’s last opera. He died of throat cancer in a clinic in Brussels in 1924, with the final scene of the opera unwritten. The final fifteen minutes or so of the opera as traditionally performed was composed by Franco Alfano, but at the first performance (conducted by Toscanini at La Scala in April 1926), the curtain came down after the death of Liù (linked as the extract below), the point at which Puccini wrote his last music.

Alfano's ending has come in for plenty of criticism, but his name has been greatly rehabilitated in recent years by the discovery that the ending as published - and as performed by Toscanini - is not the ending as written by Alfano. Toscanini disliked Alfano and inflicted heavy cuts on his contribution to the score, which goes a long way to explaining why the opera seems to end so quickly with a perfunctory resolution of the tension between Turandot and Calaf. Alfano's original ending has been published and recorded and it is definitely better than the truncated version left us by Toscanini. Whether it becomes accepted by opera companies and audiences it another matter entirely.

Puccini’s gifts for drama, timing, melody and musical logic have justly made him one of the most important composers in operatic history. I hope this survey has encouraged you to explore some of the lesser-known corners of his output. We’d certainly be the poorer without him.

This article is based on a Keys To Music program first aired on ABC Classic FM (now ABC Classic) in November, 2008.

Comments